Claxton Opera

History

(Taken from “Claxton – A Thousand Years of Village Life”)

Part One - The Meeting House

The first Baptist chapel in Claxton (Strict and Particular) was founded largely by the efforts of Mr Henry Utting, the first pastor who bore most of the principal expense himself.

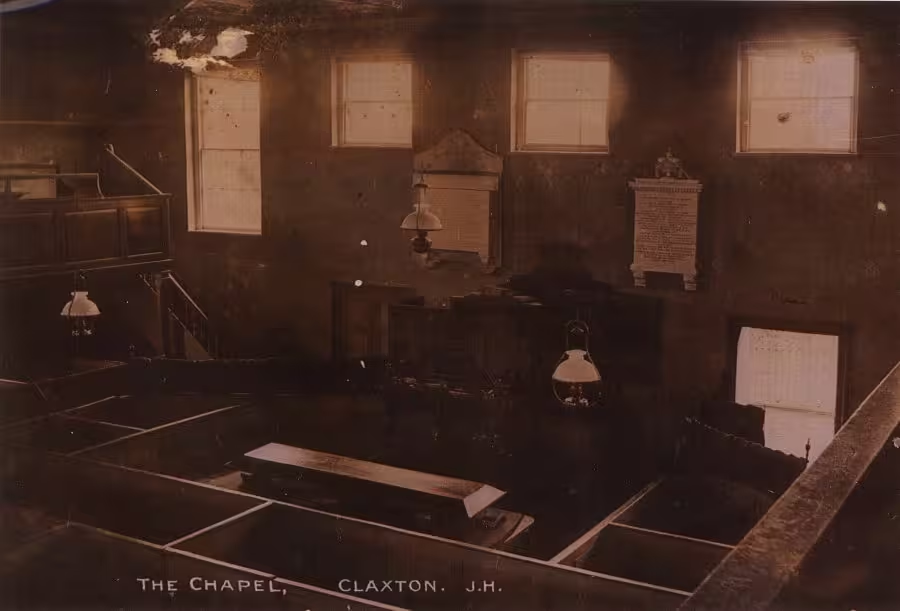

The original deeds of the Meeting House, destroyed in the disastrous fire of 1993, showed that the present building was erected between 1750 and 1755. The deeds were witnessed by five members of the congregation, four of whom could not even write and marked it only with an X. Such chapels or meeting houses were often built slightly out of the village on land which could be purchased more cheaply. The land was let at first by a local farmer at a peppercorn rent and only granted as freehold in 1779.

The expert opinion, when the building was assessed for listing in the late 1960s, indicated that the lean-to on the west side of the building was part of an earlier chapel or meeting house. It is possible that the main building itself was altered in the early nineteenth century. Certainly the bricks of the lean-to are significantly older than those of the main building and the upper courses of the latter indicate further alteration. The money for the Meeting House was provided largely by the Countess of Huntingdon, a legendary figure and one of several aristocratic women who were prominent in the history of the Baptist Movement. She became the focus of a considerable congregation of members who sought a reformed and more extreme form of worship and lifestyle. Her following became known as the Countess of Huntingdon’s sect.

Claxton could boast one of the biggest Strict Baptist churches in the district. Some of its earliest members walked more than 12 miles from the Beccles area to attend services. The Meeting House in its original form certainly reflected the sect’s aims. While embodying the ideals of Georgian architecture it remained very austere and plain. Such decorations as there were resulted more from function than from vanity or mere show. Even the door-jambs and doors were re-used from an earlier building. Some examples still exist in the present structure.The panelling of the gallery that ran round three sides of the building and the pulpit were constructed in pine using the plainest possible design. A twenty foot section of this is also still intact.

Standing 45ft square and 18ft high the chapel accommodated five hundred in its heyday, which is remarkable given that current safety requirements permit an audience of just 104 at the annual opera nights. The doors at the front kept the sexes strictly segregated. Bodily ornament was condemned. Women kept their eyes lowered. Sunday morning service lasted three hours. A great clock faced the pulpit and sermons often lasted over an hour. Many picnicked in the summer and took refreshment at long tables in the winter, before a further two hour service in the afternoon.

The most famous minister, Job Hupton began his ministry in September 1794. He was a fire and brimstone preacher and wrote spirit lifting hymns, such as Come ye faithful, raise the Anthem. When he died in October 1849 at the end of a long ministry, he was buried in the Meeting House graveyard alongside two of his wives. He was succeeded by Mr David Pegg who was pastor for 20 years and then by Mr Henry Pawson.

Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century the Meeting House flourished, as the burials indicate in the adjacent graveyard. However the first blow came with the huge expansion of Methodism, and when the Oxford Movement rejuvenated the Church of England it further squeezed the more extreme religious sects. The most devastating blow was the emancipation of working people brought about by the social dislocation of the First World War. The ordered world of deference, privilege and authority was crumbling and people were looking elsewhere for meaning in their lives.

The Meeting House closed for worship in 1943 and was sold to local farmer Mr Leslie Catchpole who used it as a tractor shed and grain store and burned the pews on his fire! The burial ground disappeared beneath a jungle of brambles, elder and rosebay willowherb and the chapel fell slowly into ruin.

In 1973 musician and teacher Richard White, returning to the Norfolk of his childhood, with his wife Roberta bought the chapel and the keeper’s cottage. The family lived in the cottage, made the chapel weatherproof and enjoyed the grand space.

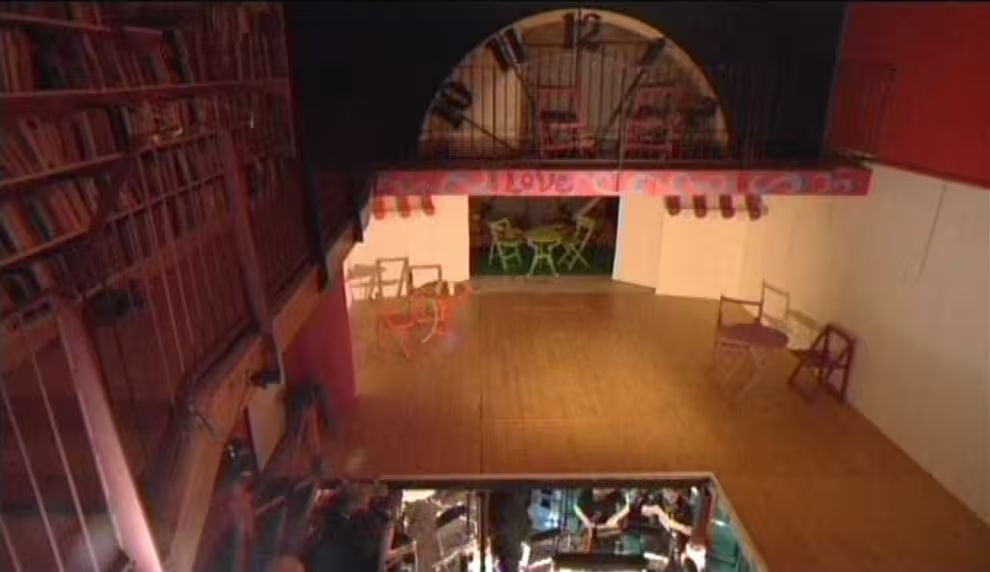

In 1983 the cottage was sold to David and Lesley Hamlyn and Richard converted the chapel into a spacious house. Ten years later the building was gutted by fire, only the four walls remaining. The Old Meeting House was rebuilt and after 18 months the family moved back into their home. A new chapter began with the fulfilment of Richard’s long cherished dreams: operas at Claxton. Since then Claxton Opera has presented one opera each year. The living room becomes a theatre for two or three months, complete with lighting rig, orchestra pit for thirty players and a gallery.

The chapel lives on resounding to a rather different sort of music from that heard in the heyday of the Strict and Particulars.

Part Two - Claxton Opera

In 1978 Major Derek Allhusen kindly agreed to a summer performance of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas in front of the castle walls at Claxton Manor. A mention on the BBC’s Look East helped sell every seat and Claxton Opera was on its way. The opening performance took place amid a warm summer gale.

The following year saw a production of Handel’s Acis and Galatea in front of Claxton Manor itself. Staged as an Edwardian House party, the performance went with a tremendous swing after Major Allhusen poured away the Ribena stage ‘wine’ and replaced it with a very acceptable Beaujolais.

The first production at the restored Old Meeting House was Don Giovanni by Mozart, which featured a powered lift to convey the Don down to hell – this slow moving device entrapped Leporello at every performance, forcing him to sing from within the cage. In 1995 there was a version of The Mikado set on the beach of a seaside town. Cosi fan Tutte, staged the following year, initiated a new strand in the Claxton story: the unending alterations of the building structure. New apertures in the north wall revealed the young warriors sailing away to war. In June 1997 came a performance of Beethoven’s Fidelio, which required yet more trap doors to be cut in ceilings and floors.

Gluck’s Orpheus and Euridice received a unique outdoor treatment in 1998, with an alfresco peripatetic performance, each act moving from grove to lawn to yet another shaded arbor in Bill and June Boardman’s beautiful garden at Bergh Apton. The next year brought performances of Britten’s Albert Herring and then Mozart’s Magic Flute in 2000. This was very different from the earlier production with the genii descending through the ceiling in a lift – a scene that required yet another new trap door!

Meanwhile a real-life drama was being played out behind the scenes. The planning rules governing the performances were very strict and the operatic activities had transgressed these, incurring the wrath of both neighbours and the local council. Briefly it looked as if the opera might close but fortunately, with renewed obedience to the guidelines, a solution was found.

In 2002 there was a return to the Old Meeting House with a performance of Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio, but a hip operation for Richard White meant that there was no production the following year. Instead, a very successful opera concert kept things going and in 2004 full service was resumed with the octogenarian Verdi’s Falstaff.

Richard White describes the annual transformation of his home into an opera house and the sense of ‘ecstasy’ that comes with each successful performance.

“I don’t suppose many people hold operas in their living rooms, but we do. For me it’s a transcendental experience. Suddenly in June each year the comfortable furniture is swept away into garden sheds. For a while the space lies empty, dust settling through the geometry of light created by our Georgian windows. Then gradually the place is filled with bits of half-made scenery, rehearsal piano, singers poring over their scores, people up ladders hanging theatre lights. More dust as the orchestra pit is swept, only now the dust dances to tentative fragments of Mozart or Verdi.

Eventually the plush pink orchestra curtains add a touch of theatrical glamour, the back-and-white chairs stand in orderly rows, the gallery glass front is polished, the fire extinguishers are hung – it’s a theatre!

The day arrives. The audience drives up from the village in mini-buses, often on a beautiful midsummer evening. They grab a glass of wine and crowd into the garden, then the bell rings and all hustle through our kitchen into the opera house. The lights dim, polite applause for the conductor and at that moment I take my own glass of wine and stand on the sunlit country lane – Slade Lane – now silent and empty. The opening bars trickle through the open doors and windows like fresh, cool water, turning swiftly into a flood, a joyous benediction over the countryside, unnoticed by the odd passing car or the cows across the valley. For me it’s ecstacy, fulfilment absolute.”

Glyndebourne and Claxton

Two English Festivals

Translation from “Strumenti E Musica” September 1996

You want Opera? Go into the Country

From our correspondent Silvano Sardi

For many interested in melodrama (opera?) particularly in Italy, the Glyndebourne Festival Opera which is held in the summer is a bit like the Arabian Phoenix: they know it exists (it’s well known all over the world) but they don’t know where it is – precisely – or even what it is. Imagine then the Claxton Opera which is another festival, which you may or may not hear spoken of in the Norwich area, but which is known only by those 104 people (not one more) who regularly attend. Since this year I have had the rare opportunity of enjoying at Glyndebourne the lightest and most elegant of Richard Strauss’s operas Arabella and at Claxton a Cosi Fan Tutte, which if Mozart had been present, knowing his liking for fun and eccentricity (and if at Claxton they weren’t overdone) he would have been highly entertained, I shall be able to give you some information about these two summer opera engagements which in my opinion gives us more than anything else a clear idea of the English Cultural Scene.

Let us say at once that these two festivals are so different in character as to render comparison impossible. The distance between them is not only geographical (one is in the south, in Sussex, below London, almost at the English Channel, the other is north of London, in Norfolk, a county which faces the North Sea). Nevertheless, they have at least three points in common which make them unique, so to speak.

1. They do not take place in large centres. In fact, Glyndebourne and Claxton are neither cities nor towns, but tiny villages. Rather, to tell the truth, they are “houses” situated close to a village. And when in England you say “house” you mean simply a building surrounded by land. It can be anything from a castle or a mansion with a park and fields/lawns as far as the eye can see, like Glyndebourne, to the most humble “floor with a roof”. The “house” where Claxton Opera takes place, is in between.

2. The two organisations perform in modern, highly functional buildings.

3. Neither festival draws from state funds, because they are “private”. “Private” for the English means “exclusive”, like a club with a fixed membership. In this case there are as many seats available as there are members. The seats are booked in advance by members, then go on sale as at any other theatre. How easy it is to get a ticket I leave to your imagination. Meanwhile, prices: in the central tier where I was (the seats are) £110, roughly 250,000l. Size:- at Glyndebourne, opera on a grand scale with great orchestras, great conductors, great singers, great production – absolute perfection. This year, besides Arabella, they have Theodora (Handel), Cosi Fan Tutte (Mozart), Yevgeny Onyegin (Tchaikovsky), Lulu (Berg), and Ermione (Rossini).

Claxton Opera on the other hand is a one-opera mini-festival. The opera is rehearsed for six months (winter – spring), and put on in the summer: six performances, in two blocks of three each in successive weeks. The choice of opera is the prerogative of the “patron”, Mr Richard White, of whom I shall tell you more. There is a small orchestra (max. 37 players) and a regular conductor.

However, despite being “mini”, even her at Claxton the requirements of sound and vision are pleasingly blended into an artistic performance, in tasteful surroundings, and this combination, in proportion, is the same in both festivals.

(5 paragraphs followed talking exclusively about Glyndebourne, the productions, restaurants, bars, intervals, picnics, evening dress, the house, lawns and leisurely tempo of it all)

How different is the case of Claxton Opera which is also a Festival Club with limited membership (and also never any empty seats) but in fact exists thanks to the love of its founder, Mr Richard White.

How different is the case of Claxton Opera which is also a Festival Club with limited membership (and also never any empty seats) but in fact exists thanks to the love of its founder, Mr Richard White.

An extraordinary man! I believe he may be about sixty but truly he doesn’t look it. He seems like a boy; always lively and apparently carefree. But he has quite a few worries nevertheless. His story is not short, like Mimi’s. Born in Norfolk, he lived until approaching retirement far away at Bury St. Edmunds.

He teaches literature but his love is singing. This he has studied seriously as is shown by his fine tenor voice, which he uses every now and then in the operas he produces. Before retiring he decided to settle finally in the area where he was born, and for this reason set about looking in the Norfolk countryside for a big house for restoration. His dream was to have a large room where one could make music, sing and meet with friends.

And at last he found it, not far from Norwich, in Folly Lane on the outskirts of the village of Claxton. It was a ruin, but had a good name and a long history. It is called The Old Meeting House. When it was built in 1735, it was a Baptist Chapel: a house of prayer. In the course of the centuries it had several uses, as a refuge, a harvest store and then as the village school. In 1934 it was finally closed. On the spur of the moment, Mr White bought the ruin, with the surrounding land including a small adjoining building which in its time had served as a stable. The first thing to be done was to make the stable habitable for his wife and one son. A grim life; outdoor sanitation, no lighting, and a leaking roof. Then the lighting came, but then also came a second child, and then two more. Meanwhile the old chapel began to take on a new shape, in accordance with the plans of our Mr White. The dreamed-of music room was emerging. Finally when it seemed the hard work was almost finished, his wife fell seriously ill (it was the first of a series of relapses which could lead to paralysis), and everything stopped. But Mr White is tough. He held firm. His wife was getting better. Hopes were raised. Just a bit more effort and we’re there!

At last! No Sir! In the middle of the night a fire sent the roof and everything up in flames. Bad luck? Fate? Malice? I am not putting forward any theory. Certainly the neighbours to this day are not completely satisfied about the noise and the coming and going of people through the countryside. Ah well! It’s true that nowadays theatres burn better than woods! Anyway, for Mr White this fire was manna from heaven. There was the insurance! The compensation was sufficient to allow for the construction of a fully equipped theatre (small – 104 seats) with an internal frame of steel and indestructible. In the summer, a theatre for six days of opera, for the rest of the year, a luxury home. The dream has become a reality. I am skimming over the thousand and one difficulties still to be resolved (…) parking, viability. At Claxton Opera you arrive via a little lane you can hardly see. We were able to find it because at a certain point, among the various handwritten notices on signposts (advertising apples for sale) we saw one on which was written (by hand!) “Opera”. We followed the sign into this little lane. Without this, who would have found it!

Mr White’s method is simple: economise, cut down on spending. He is director, organiser and “trovarobe” (finder of stuff?). When necessary he also covers the tenor role. A friend does the lights, the stage manager is a lecturer at the University (!) who enjoys doing it. Then there are membership fees, ticket prices, voluntary helpers. The orchestra is composed of old (retired?) teachers and music students. The former he pays Union rates, the latter a few pounds (this is training for them). He selects the singers according to the opera in hand, but not only does he not pay them, he requires from them £25 a head, if they want to sing. I’m talking about “boys” and “girls” who have studied (music) but then gone on to other things – good, nevertheless. The delicious voices of Fiordiligi and Dorabella in this year’s Cosi Fan Tutte, for example, belong to two assistants in a big record shop in Norwich (!). This year Mr White has done it on £5000 – not 15million. This all went on the orchestra (the majority), scenery, costumes and odds and ends. I sometimes think of the richness of human (talent) which we have but do not know how to exploit. (I know this is Utopia). Yet we in Italy could also achieve something of the kind with who knows how many retired and bored music teachers, music students with nowhere to practise, and “voices” being wasted in other jobs. What a wonderful hobby it would be.

Meanwhile, by this means Mr White has already produced a fine series of shows. While awaiting the reconstruction of the house, after the fire – talk about enthusiasm – he started in Norwich theatres: The Magic Flute (Mozart) at the Theatre Royal in 1985, Orff’s Carmina Burana in St. Andrew’s Hall in ’88. Then in ’92, with the formation of Claxton Opera, Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro at the Thorpe theatre (?) – and finally he inaugurated the rebuilt Old Meeting House at Claxton with Don Giovanni (Mozart) in ’94 followed by The Mikado of Gilbert and Sullivan in ’95 and this year Cosi Fan Tutte. And in this unusual Theatre-House, I enjoyed the Mozartian masterpiece. No need to yearn for the great orchestral sound – it was certainly not that of the London Philharmonic, nor for the grand maestro’s baton, nor for the strict correctness of the original language (anyway, how many Italian “Carmens” do we see in Italy?). I enjoyed it without being exasperated by that crescendo (which here one would like) wedged between two sotto voce in the terzetto “Una bella serenata”; without “Come scoglio”, and also without the emergence of that mocking sound of oboe and clarinet which in the final sextet marks the pitiful outcome of the cruel game. We enjoyed it (and the 104 audience applauded vigorously) because we felt that we were with Mozart’s masterpiece in the same surroundings. Free from intellectual prejudice, spiritually well-disposed. Thus, between the fascinating melodies of Fiordiligi and Dorabella and the bitterness of Despina’s arias, the mystery of the “dramma giocosa” of the late 18th century in which can be discerned the shadow of Sade, sent us from the “house” with our spirits troubled but satisfied.

Don Prutton

28/11/96